When studying virus infection (or, in fact, any complex biological phenomenon), it is natural to wonder whether the cell system of choice adequately recapitulates the complexity of an organism. This is also true for respiratory infections, where not only the airway epithelium is made up of a multitude of different cell types, but also mucus is present, and the cells themselves are exposed to air rather than media and unique mechanical forces. That’s where a method called the air-liquid interface (ALI) model becomes helpful.

The Air-Liquid Interface Model

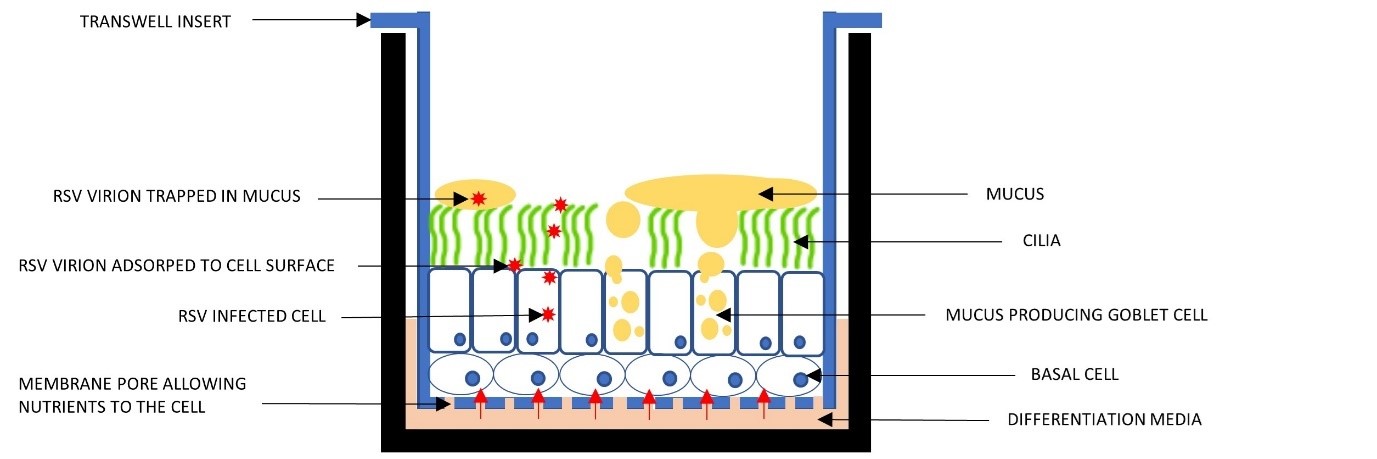

The ALI model is a non-submerged culture system where one side is exposed to humidified air, mimicking a human airway’s physiological environment. This model emulates the diverse cellular composition of the airway with a platform of basal cells supporting multi-ciliated, goblet, and less common yet vital cells. These rarer cells, such as club, tuft, or brush cells, and ionophores, may play a significant role in respiratory diseases. In ALI cultures, cells develop cilia that beat rhythmically and move mucus, air, and particles as they would in airway epithelia.

The ALI model is suitable for studying the pathogenesis of various viruses, including Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). In this article, we will describe some of the techniques we employ at Virology Research Services to visualise and quantify RSV infection using the ALI system.

RSV Infection and the Air-Liquid Interface Model

Below, we give a detailed account of how we utilize the ALI system to visualize and quantify the impact of RSV infection. We will start with a brief overview of how ALI cultures are generated, but you can read more about the ALI model in our previous blog article.

Growing Cells from Frozen Pellets

The process begins with cells stored as frozen pellets in liquid nitrogen for long-term viability. These cells are then carefully defrosted.

Placing Cells in Specialized Medium

Next, the cells are transferred into a flask containing a warm, specialized medium. This environment encourages rapid cell growth, known as the expansion phase. To ensure healthy growth, the flask’s surface is coated with a collagen solution, enabling the cells to embed into it.

Transitioning Cells to Transwells

Once a sufficient number of cells have grown – typically in the millions – they are ready for the next step. They are detached from the flask and placed into small baskets known as transwells. In this environment, cells continue growing until they cover the entire surface.

Understanding the Transwell System

Each transwell has tiny pores, 0.4 μm in diameter, allowing nutrients to flow from the media to the cells. These baskets are suspended above the plate base, keeping the cells in a submerged culture with the medium both above and below.

Figure 1. The ALI Transwell system.

Achieving Confluency in Cells

After the cells have grown enough to cover the transwell base, a process known as achieving confluency, we introduce a significant change. The liquid covering the cells is removed, exposing them to air.

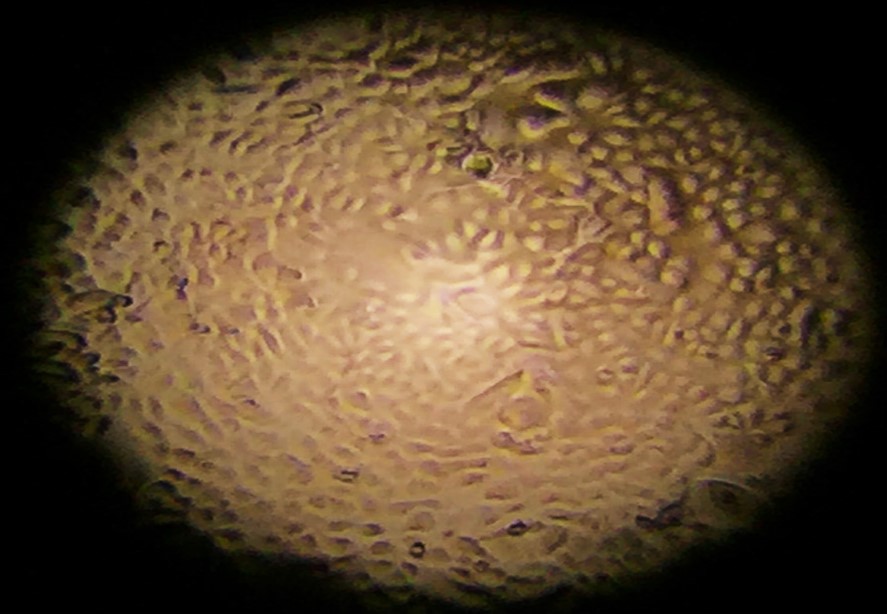

Figure 2. Cells growing before they reach confluency and are exposed to air (note the “cobblestone” appearance).

Switching to a Specialised Medium

The basal medium is then replaced with a more specialized medium. This unique medium contains a blend of hormones and additives, driving the process of differentiation in the cells.

Observing Changes and Preparing for Infection

Within one to two weeks, changes become apparent. The surface starts appearing glossy, indicating mucus production by the goblet cells. This glossiness also suggests that differentiation into other cell types is underway.

Cilia Formation

Once another week or two has passed, it’s time to get a closer look. By using a light microscope, we can observe the formation of cilia in our Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) model. Cilia are small cellular projections that play a crucial role in cell functionality. They beat backward and forward around 10–20 times per second, effectively moving mucus around. See video below.

Preparing for Infection

Before we initiate the infection in our Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) model, it’s critical to minimize the mucus presence. A high mucus concentration could hinder the virus from reaching the cells.

To this end, we perform several gentle washes of the cell surface, typically using a warm medium for 20-30 minutes.

Introducing the Virus

Following the washes, we add the virus, usually adhering to a predetermined multiplicity of infection (MOI) ratio. This ratio signifies the number of infectious virions per cell – a higher MOI means more virus particles are added. In these experiments, we always include a mock control – a setup where no virus is added. This control provides a valuable comparison against the infected wells.

Adding Test Subjects or Compounds

Before or after infection, we can also introduce test subjects or compounds. We adjust for the additional volume of the viral input to maintain accuracy in our experimental setup.

Incubating the Cells

After adding virus to the transwells, we incubate for at least two hours at physiological temperature. This period allows the virions to reach the cells and attach or fuse.

Tracking the Infection

Post-infection, any unbound RSV is removed through additional washes. The cells can then be incubated for the desired period, and a surface wash can be performed daily, if needed, to track the viral release from infected cells via qRT-PCR or quantification of infectious virus.

Visualizing the Infection

At the end of the experiment, the cells can be fixed in 4% formaldehyde, which preserves their structure and renders all viruses non-infectious. This procedure prepares the cells for imaging using immunofluorescence.

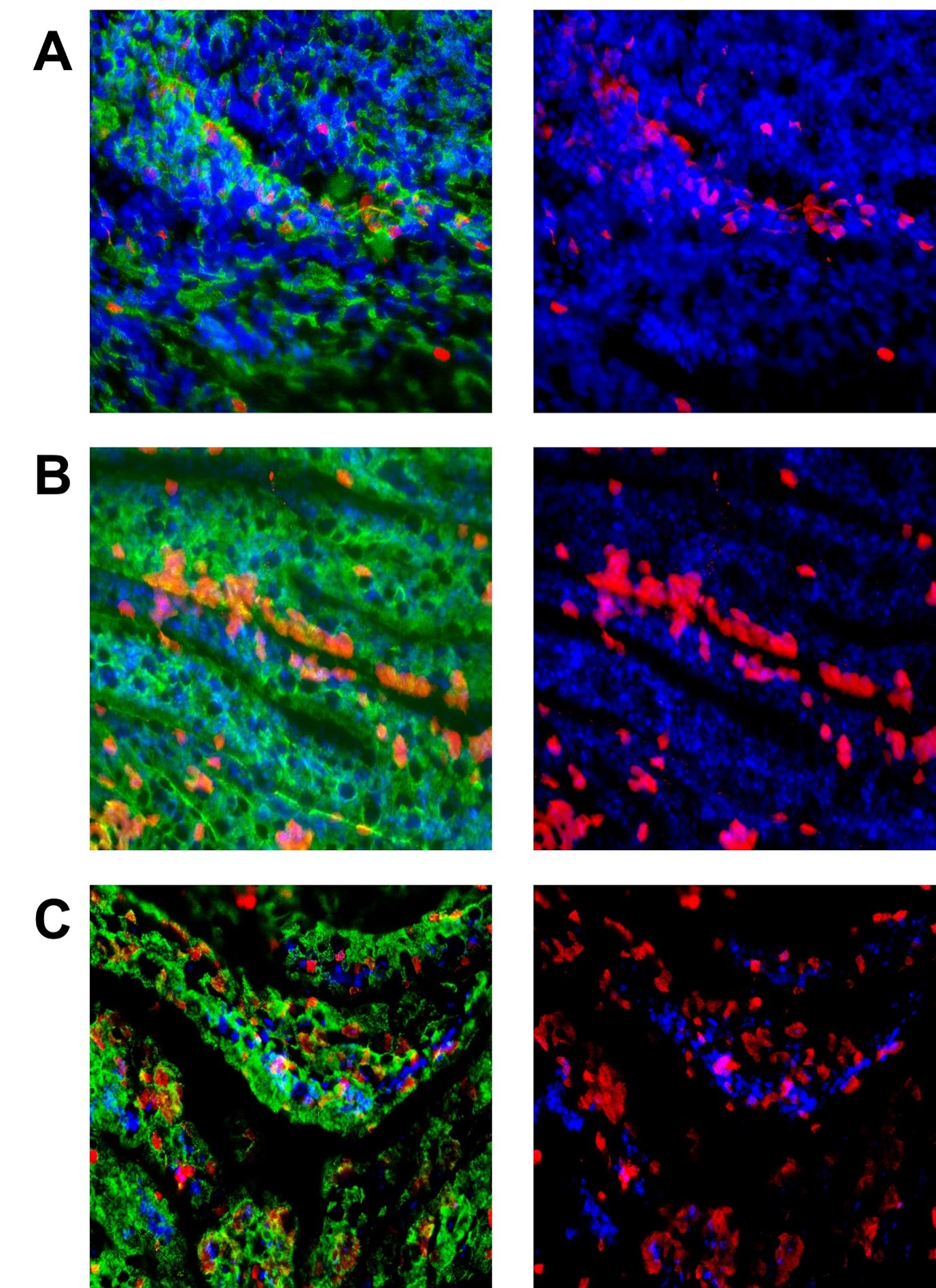

Immunofluorescence is a method that employs highly specific antibodies to certain proteins and then adds different coloured fluorescence via a secondary antibody. In the images below, RSV was stained with an anti-RSV antibody, followed by a red secondary antibody.

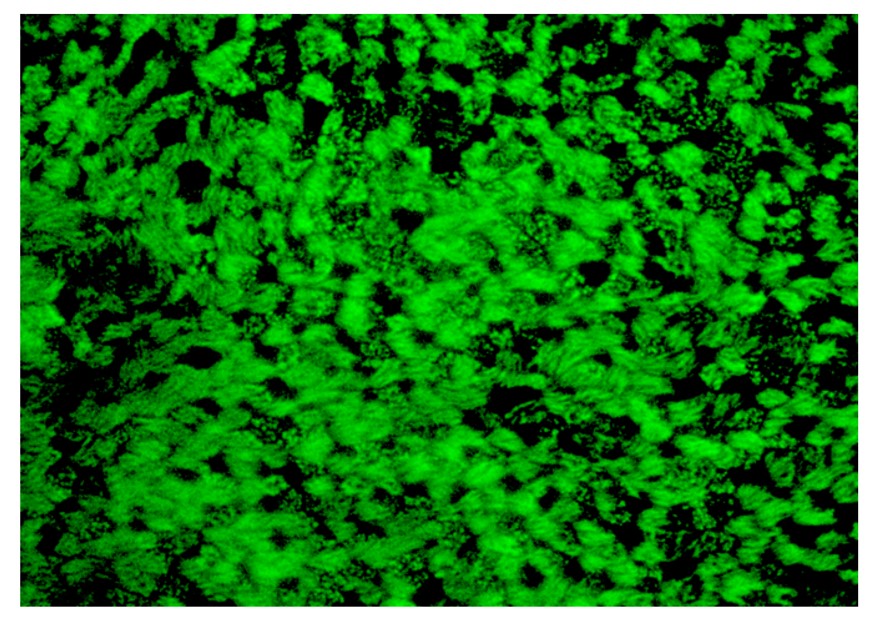

In parallel, an antibody to the cilia was used to check the condition of the cells, which fluoresce green in the image below. Infected cells may eventually lose their cilia, which can also provide an indication of infection.

Finally, Hoechst stain (blue) was used to visualise cell nuclei.

Figure 3. The surface of the transwell stained to show the cilia (green). Each group of cilia represents one cell. Individual cilia can be seen. This image is from a mock infection, where no virus was added.

Figure 4. This set of images is of ALI cells exposed to different MOI of RSV. They were exposed to the virus for 2 hours before washing and left for 72 hours. The green in the pictures on the left is the cilia (acetylated tubulin), and the right pictures have this removed so the infected cells (in red) can be seen easier. Cell nuclei are in blue. Panels A, B, and C show MOIs of 0.3, 0.5, and 3).

Quantifying infection

A quantitative assessment can also be made by using qRT-PCR and/or quantification of infectious particle release. Cells washes taken either at the end of the experiment before fixing or at defined time points during the infection can be used to collect virus released from the apical surface of the infected cells. This virus can be quantified both by qRT-PCR, using a validated set of primers, or by TCID50, whereby the ability of the collected virus to infect and kill a fresh monolayer of permissive cells is quantified across multiple virus dilutions. Differently from qRT-PCR, which quantifies genome copies, the TCID50 quantifies only infectious particles. A discrepancy between the two can also provide important information on virus stability or on the mode of action of a test compound.

When quantifying virus release with one of these two methods, it is important to also collect and analyse the virus present in the last of the washes performed at the end of the two hours infection: this amount represents a baseline over which actual virus replication can be scored. This is important to avoid misleadingly interpreting residual virus from the initial inoculum as replicating virus.

Conclusion

By utilising the air-liquid Interface (ALI) model, we can observe the real-time infection of the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) on a representative model of the human bronchial airway. This method paves the way for new avenues in studying RSV and potential interventions for respiratory diseases.

Explore the potential of the ALI model in respiratory disease research with our experts at Virology Research Services. Contact us today and advance your study of RSV and beyond.

Blog by Paul Griffin

Edited by Reckon Better Scientific Service