Figure 1. Major viral morphologies showing the diversity of viral structures. From top to bottom: helical naked virus (Watermelon Mosaic virus), helical enveloped virus (Influenza), icosahedral naked virus (HAV, Hepatitis A virus), and icosahedral enveloped virus (HSV, Herpes Simplex virus). Note the presence of surface proteins (purple) that facilitate cell entry.

The Challenge of Cell Entry

Viruses face a fundamental challenge: they must transfer their genetic material across the protective barrier of the cell membrane. This process requires precise molecular coordination between viral proteins and cellular components. The virus must not only identify the right cell type but also trigger the appropriate entry pathway while avoiding host defensive measures.

Recognition: The First Critical Step

Cell entry begins with highly specific interactions between viral surface proteins and cellular receptors. Viruses have evolved to recognize cell-surface apparatus – the structures that viral particles can recognise is very diverse, their targets can be cell surface protein receptors, for example, the CD4 receptor of T lymphocytes, or glycans, for example the sialic acid modifications on respiratory epithelial glycoproteins for influenza. Glycans are present on all mammalian cells, but with specific terminal structures that vary between different tissues and species.

The specific terminal structures present on a cell differs between cell types – the structures a virus can recognise determines its tropism. For example: HIV targets the CD4 receptor on immune cells while influenza viruses, recognize sialic acid modifications on respiratory epithelial glycoproteins. This specificity explains why different viruses have different tropism or cause distinct patterns of disease.

The Dance of the Spike Protein

Recent structural studies have revealed fascinating insights into how viral proteins prepare for cell entry. The SARS-CoV-2 virus provides an excellent example: its spike protein exists in either “open” or “closed” conformations, much like a molecular door that must open to allow infection.

What’s particularly interesting is how this mechanism has evolved through variants. The original virus maintained a careful balance – about half its spike proteins were closed, half open. But newer variants show a striking shift toward the open state. The Omicron variant, for instance, much favours its spike proteins in the “open” position (reviewed by Le et al. 2023).

This is significant because “open” spike proteins are ready to interact with our cells immediately upon contact – imagine having all your keys already extended and ready to unlock a door versus having to pull them out of your pocket first. This increased readiness helps explain why newer variants can infect cells more efficiently and spread more rapidly between people.

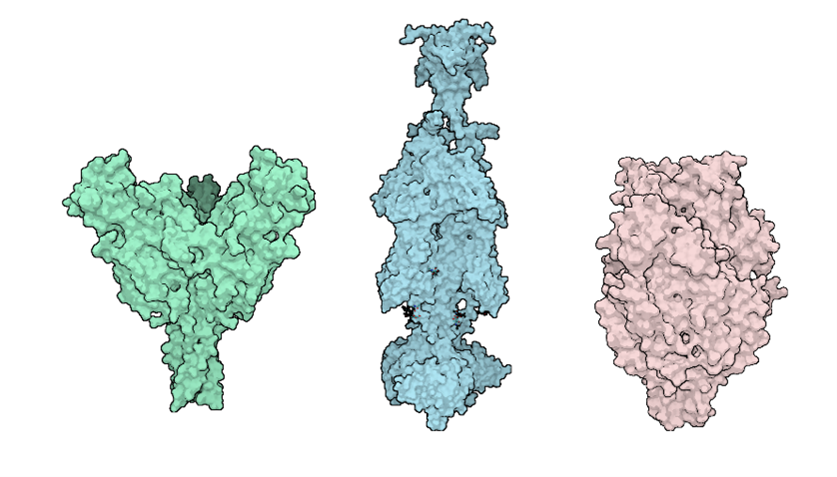

Figure 2. Structural comparison of viral fusion glycoproteins. Left to right: Ebola virus glycoprotein (green, RSCB: 5JQ3), Herpes Simplex Virus glycoprotein (blue, RSCB: 5V2S), and Respiratory Syncytial Virus fusion protein (pink, RSCB: 8YE3). These proteins undergo dramatic conformational changes to facilitate membrane fusion during viral entry.

Primary Entry Pathways

Once a virus has identified its target cell, it can utilize various distinct entry mechanisms :

Membrane fusion

Enveloped viruses can directly bind to and bypass the lipid bilayer of a host cell. Viral membrane fusion proteins (fusogens) facilitate this process by lowering the kinetic barrier of the bilayer – the fusogens bind to the host cell bilayer, undergo a conformational change and fuse the two bi-layers together. Fusion of two bilayers is thermodynamically favourable but there is a high activation energy required to do so. The fusogens facilitate this by using the free energy released during their conformational changes to draw viral and cellular membranes together which then fuse. The fused lipid membranes of the host cell then create a fusion pore in which the genetic material of the virus can be deposited.

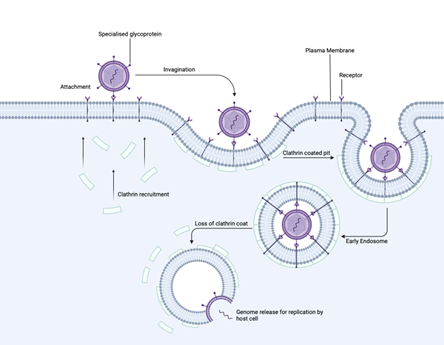

Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis serves as a fundamental cellular uptake mechanism that viruses have evolved to exploit. This process normally internalizes receptor-bound molecules essential for cell function, but viruses can hijack it by mimicking legitimate cargo. When a virus binds to specific cell surface receptors, it triggers a signalling cascade that recruits clathrin proteins to the membrane’s internal face. These clathrin proteins assemble into characteristic coated pits that progressively invaginate and pinch off to form virus-containing endosomes. As these endosomal vesicles mature, they shed their clathrin coat and become increasingly acidic – a pH change that often acts as a molecular trigger for viral uncoating and genome release. While both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses can utilize this entry pathway, some viruses require additional endosomal proteases to successfully deliver their genetic material.

Figure 3. Step-by-step illustration of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The process begins with viral attachment via specialized glycoproteins, followed by clathrin recruitment and pit formation. The virus-containing vesicle is internalized and loses its clathrin coat, ultimately leading to genome release within the early endosome.

Caveolar Entry

Certain viruses preferentially enter cells through caveolae (meaning “little caves”) – specialized cholesterol-rich membrane domains that form distinctive flask-shaped invaginations. This pathway, particularly well-characterized for non-enveloped viruses like SV40, serves as more than just an entry portal; caveolae function as major cellular signalling hubs that viruses have learned to manipulate. For example, SV40 actively triggers rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton at entry sites and stimulates the phosphorylation of caveolin proteins, enhancing caveolar dynamics to promote its infection. Unlike the clathrin-mediated pathway, caveolar entry maintains a neutral pH environment throughout the internalization process. Instead of acidic endosomes, viruses are delivered to specialized pH-neutral organelles called caveosomes, where their contents are sorted and directed to appropriate cellular compartments – in SV40’s case, the nucleus for genome replication.

Endosomal Entry

A newly understood pathway shows remarkable flexibility in viral strategy. In the case of SARS CoV2: when the typical entry mechanism is blocked due to low levels of the enzyme Transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) on the cell surface, the virus can switch to an alternative route through cellular compartments called endosomes. In this backup pathway, a different enzyme – cathepsin L – helps trigger the virus’s entry machinery. This dual-pathway strategy showcases viral adaptability: by being able to use either TMPRSS2 or cathepsin L to initiate entry, the virus can successfully infect a broader range of cell types, even when they have different enzymes available.

Micropinocytosis

Micropinocytosis is another cellular process that viruses use to gain entry into its host. Micropinocytosis (or macropinocytosis, for larger-volume fluid uptake) refers to a non-specific form of endocytosis in which cells engulf fluid and particles in relatively large vesicles. Several viruses (Vaccinia virus, Coxsackievirus B, and certain filoviruses like Ebola) can induce or hijack macropinocytosis. This usually involves a large ruffling of the plasma membrane that engulfs the virion in a fluid-filled vesicle.

The Critical Moment: Uncoating

The culmination of the entry process is uncoating – the controlled disassembly of the capsid we explored in our previous article. New research has revealed the intricate molecular choreography of this step. The virus’s proteins undergo dramatic rearrangements, anchored by specific structural elements including a three-stranded molecular “backbone” and stabilizing chemical bonds. These changes ultimately bring the viral and cellular membranes together, allowing fusion and delivery of the viral genome.

The process involves several triggers:

• Endosomal acidification can induce conformational changes in capsid proteins

• Cellular proteases may systematically dismantle the capsid

• Interactions with specific cellular factors can trigger controlled disassembly

Implications for Therapeutic Development

Understanding viral entry mechanisms has profound implications for antiviral development. Each step – from initial recognition to final uncoating – represents a potential therapeutic target. For example:

• Entry inhibitors can block receptor binding

• Endosome acidification inhibitors can prevent uncoating

• Protease inhibitors might prevent necessary capsid processing

Ask how we can help

Are you developing antivirals targeting viral entry? Our team can help evaluate your compounds using advanced cellular entry assays. Contact us to discuss your research needs.

Blog by Caroline Chapman

Assisted by Reckon Better – Scientific Communication Specialists